Nick Hornby is the bestselling author of novels including About A Boy, High Fidelity, and Fever Pitch. Titles ripped from Elvis Costello lyrics aside, he is also, if we are to take his comments at the Cheltenham Literature Festival to heart, an advocate of the simple pleasures of reading. Here, “simple” is the operative word, because the popular writer doesn’t believe that readers should attempt to finish so-called “difficult” novels, if they don’t start to enjoy them within the first few pages or chapters.

Now, I may not be a bestselling novelist, but to me, this is a potentially damaging view to take.

Reading to be Lost

Many of us read as a form of escapism. Readers, as a collective, intuitively know that a strange telepathy is at work when we dive beneath the wordsea of a really good book. For however long we stay submerged there, the writer’s codices match our own visual and emotional absorption into the text point-for-point. In fact, this phenomenon has been described, characteristically eloquently, by Will Self in one of his most recent articles for The Guardian – and I’ll stop paraphrasing it if you start reading it.

Reading to become lost in a different world, or to know a new set of characters intimately – and often far more deeply than we know our own friends – is, of course, one of the great joys of picking up a book with a rollicking narrative.

With this in mind, I’m not going to attempt to argue that there isn’t a place for this kind of reading. As a child of the 1990s, like most readers my age I harbour an enduring love for the Harry Potter series, with all of its borrowings and simplistic prose combining to make a bloody good story nonetheless.

Similarly, my own guilty pleasures are fantasy novels – and I read them across the spectrum. From the insightful sci-fi of J.G. Ballard, to the frankly painfully populistic imaginings of Suzanne Collins, my love of a decent dystopia, utopia, or Tolkien-style fantasy epic, unfortunately does not discriminate based on talent. But here is where my agreement with Nick Hornby ends.

Diving More Deeply

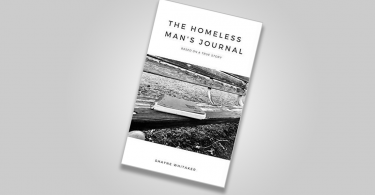

To read as a utilitarian, purely for pleasure, is no bad thing. But as I said in an earlier article on Hilary Mantel’s assassination short story, words are power, and ideas have influence. Without serious literature – and by this I mean works such as Ulysses, The Master and Margarita, and even, if the Bronte’s float your metaphorical boat, Wuthering Heights – human life would remain unexamined.

In this sense, Kafka’s argument still stands. Great literature is “an axe to break the frozen sea inside us”. Numerous psychology studies in recent years have proven this claim, by revealing that readers of literary fiction posses greater tolerance of different people and races, heightened empathy, and a far higher emotional intelligence than those who only read mainstream “stories”.

A Worthwhile Expedition

To complain that reading a book like Ulysses is difficult, is the literary equivalent of complaining that Everest is hard to climb. Some of the most valuable experiences of our lives are won through hard work, concentration, and perseverance. And what’s more, once completed, these endeavours often turn out to be some of the best and most rewarding undertakings of our lives.

As a teenager, I read Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 for the first time. Close to 200 pages in, I was still hopelessly lost and thoroughly beleaguered in his vertiginous narrative. In all honesty I very nearly gave up, until a short while later, something miraculous happened. Heller’s narrative suddenly converged, and it was as if someone had turned on a light.

Suddenly, everything became clear. The whole imagined world opened out in front of me, and from that moment I raced through the book alternately laughing, crying, and running an incessant inner-monologue which screamed, disbelievingly, “HOW DID HE WRITE THIS?”.

I still don’t know, but I do know how I read it. I read it with difficulty, and it is categorically one of the best – and certainly most productive – things that I did in my teenage years. The scale of some of the best known works of literary fiction is awe-inspiring, and the challenge of reading and understanding them is both a test and an expansion of capability.

Reaping the Rewards

Difficulty, I would argue, is in fact a necessary consequence of valuable innovation. Knowledge, skill, and pleasure are bought by hard work, and you don’t get something for nothing. Nabokov famously sneered at people who “talk about books instead of talking within books”, and this is, I assume, what Nick Hornby is advocating.

For me, literature is a method and a manner of better living. It both threatens and amplifies the ways in which I see the world, and I’m yet to find a reason why anyone would want to shy away from the agitation and dislocation that serious literature can evoke.

So, my apologies to Nick Hornby. As charming and successful as his novels are, I would far rather live in a world where people were encouraged to read Ulysses, than one in which About A Boy is the pinnacle of a reader’s ambitions.