I felt a shiver run down my spine as I wandered through the parsonage that was once the home of the Brontë family in Haworth, West Yorkshire. The thought that this furniture, these books, and these letters around me were once the treasured belongings of one of my favourite authors, Emily Brontë, amazed me.

As a huge fan of the literary classics, I was in my element knowing that I was in the exact room where Wuthering Heights was imagined and created. The grand dining table, with writing materials scattered over it, just as it would have been over 100 years ago, stood in the centre of the cosy little room. The walls were decorated in a pretty burgundy and white wallpaper, and on each side of the 19th-century fireplace were two walls completely filled with books.

However, my excitement was dulled by a sense of sadness and almost eeriness, by knowing that this dining room where I stood was also the place where the creator of one of my favourite novels passed away.

Difficult woman

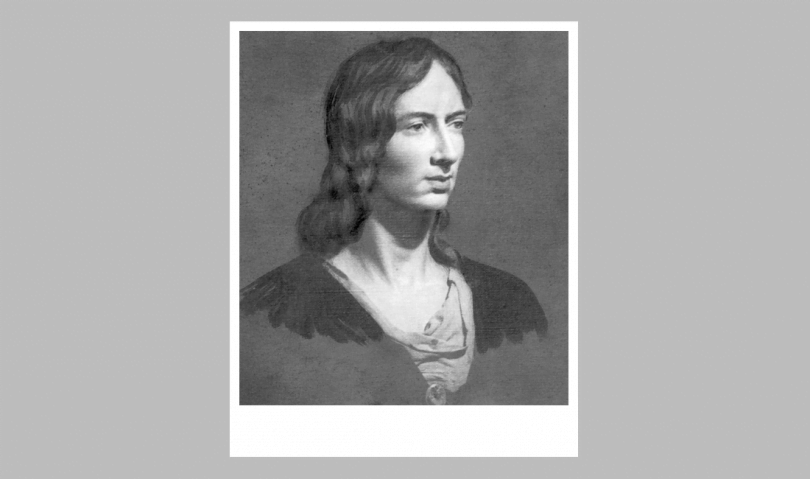

After the celebration of the bicentenary of Emily Brontë’s birth in July this year, questions have been raised about what really lies behind the public’s perception of her. Many see her as a reserved, lonely spinster who spent all her days in the company of her sisters and her dog. Others believe she was a stubborn and difficult woman, and she’s even been criticised for being masculine. But what I want to know is; what was Emily Brontë really like?

So evocative: “Before I arrived in sight of it, all that remained of day was a beamless amber light along the west: but I could see every pebble on the path, and every blade of grass, by that splendid moon.” – Emily Brontë, Wuthering Heights ??? #Brontë200

— Dr Claire O'Callaghan (@drclaireocall) August 31, 2018

Since her death in 1848, a number of damaging myths about her personality have emerged. Dr Claire O’Callaghan, a lecturer at the University of Loughborough and a Brontë expert, tells me: “For nearly 20 years the idea of ‘Brontë mythology’ has been explored and yet, mythological ideas about each member of the family- although especially Emily- still remain.”

Emily has quite often been referred to as “the weirdest of the three weird sisters” and, after reading some of the stories about her, it’s no surprise that this idea of her has been maintained in the minds of the public. People say that Emily was once bitten by a stray dog whilst walking on the moors and, keeping the injury a secret, walked home and used a red-hot poker to cauterise the wound herself, rather than seeking medical help. Similarly, rumour has is that she once beat her pet dog’s face to a pulp with her bare hands, as punishment for him jumping up onto the beds.

However, O’Callaghan tells me that many of the stories we hear about the author may not be true.

“Elizabeth Gaskell was Charlotte Brontë’s first biographer who, in the service of elevating Charlotte, opted to denigrate all those around her, including Emily. Her ideas were formed without her ever having met Emily, which seems fairly biased to me. From there, the ideas about Emily have grown and sedimented.”

In O’Callaghan’s latest book on Emily Brontë, she writes about how, over the years, Emily has been portrayed as psychologically unstable without an awful lot of evidence. Three mental illnesses in particular have been associated with the author: agoraphobia, anorexia and Asperger’s syndrome. Agoraphobia refers to the extreme fear of open or public places, and it’s no secret that Emily was a “painfully shy and socially awkward” woman, who loved spending time at home in Howarth, wandering the moors on her own. She was also sent away to boarding school at the age of six but returned to Howarth after three months, as her homesickness left her physically and emotionally upset. However, O’Callaghan dismisses the diagnosis of agoraphobia, saying that, “to me, the development from recluse to agoraphobic is an overstatement.”

Anorexia

As for the notion that Emily was anorexic, O’Callaghan explains that this diagnosis is based on Charlotte Brontë’s recounts of times when Emily was unwell. Evidence suggests that Emily starved herself when sent away to school, and the theme of starvation also occurs in Wuthering Heights, so it’s easy to see where people got this idea from. But again, O’Callaghan is keen to show that this diagnosis is purely an over exaggeration, as she questions, “Who doesn’t stop eating when they’re feeling unwell?”

It seems that Emily could do nothing without it being hugely misinterpreted by the people around her, leading to a considerable impact on her reputation. “To diagnose Emily with autism, anorexia or Asperger’s when it relies on casual observation and unreliable information is nearly impossible, especially when the information we have about her is so sparse,” O’Callaghan explains.

So, in the face of all the negative stories about Emily Brontë, what positive ideas of her personality and character have emerged? For one, it’s easy to see that she was a woman ahead of her times. “I think it is difficult to consider her as a Victorian woman writer without seeing her as a protofeminist,” O’Callaghan says. “Emily was writing about female led worlds from her youth- this in itself is remarkable.”

But as well as acknowledging that she based her narratives dominantly on females whilst living in a patriarchal society, it’s important also to recognise the type of female Emily was writing about. “Rarely are her fictional women just pretty playthings on the arms of men,” Claire assures me. And I can see exactly what she means; just look at the character of Isabella Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights. “Her narrative is a tale of domestic abuse and violence,” Claire explains. “To me, it is difficult not to see Emily’s life, and work, as an extended battle against restrictive gender norms and societal issues that oppress women.”

Rural Yorkshire

The romantic, idyllic vision we have of Emily wandering the moors in rural Yorkshire is a stark contrast to the harsh and damaging rumours that have arisen about her. Instead of accepting these myths, O’Callaghan believes we should challenge them and see her as “strong, self-assured and caring.”

And now as I reflect upon the time I spent at Haworth, in the rooms where she wrote, where she slept and where she cooked, I realise that the impression I had of Emily back then has now completely changed. It appears to me that she was just greatly misunderstood; she wasn’t a strange woman who didn’t conform to societal expectations, she was actually a strong willed, sensitive and revolutionary woman. But despite the battering her character has taken over the years, she still stands strong as the author of one of Britain’s best loved literary classics and, undoubtedly, always will.