Last month, outrage over the sexual assault allegations against Harvey Weinstein has led a lot of people to question themselves about why sexual violence, in this case, went unreported and unpunished for such a long time. We speculated about why the targeted women didn’t come forward and didn’t bring a lawsuit against their attacker.

I think this is rooted in the notion that once a case is brought into the courtroom there will be a fair sentencing which will give the victims their long-deserved justice. However, in some cases, a trial doesn’t mean that the offender will serve time, and the justifications presented for that show the underlying misogyny that is still alive and well even in our so-called progressive societies.

Because I was shamed and considered a "party girl" I felt I deserved it. I shouldnt have been there, I shouldn't have been "bad" #metoo

— #EvanRachelWould (@evanrachelwood) 16 de outubro de 2017

Since the beginning of this year, we’ve witnessed some appalling remarks being made by the people we trust to apply the law, and to punish those who disrespect it—judges. Cases of judges, both male and female although more often than not the former, who have in the course of trials justified crimes of domestic violence and sexual assault aren’t as uncommon as one might think, nor are they confined to “third-world” countries.

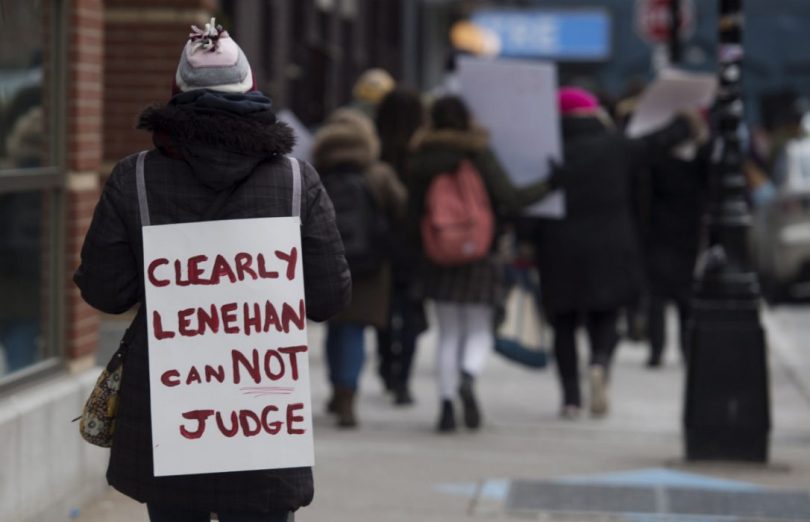

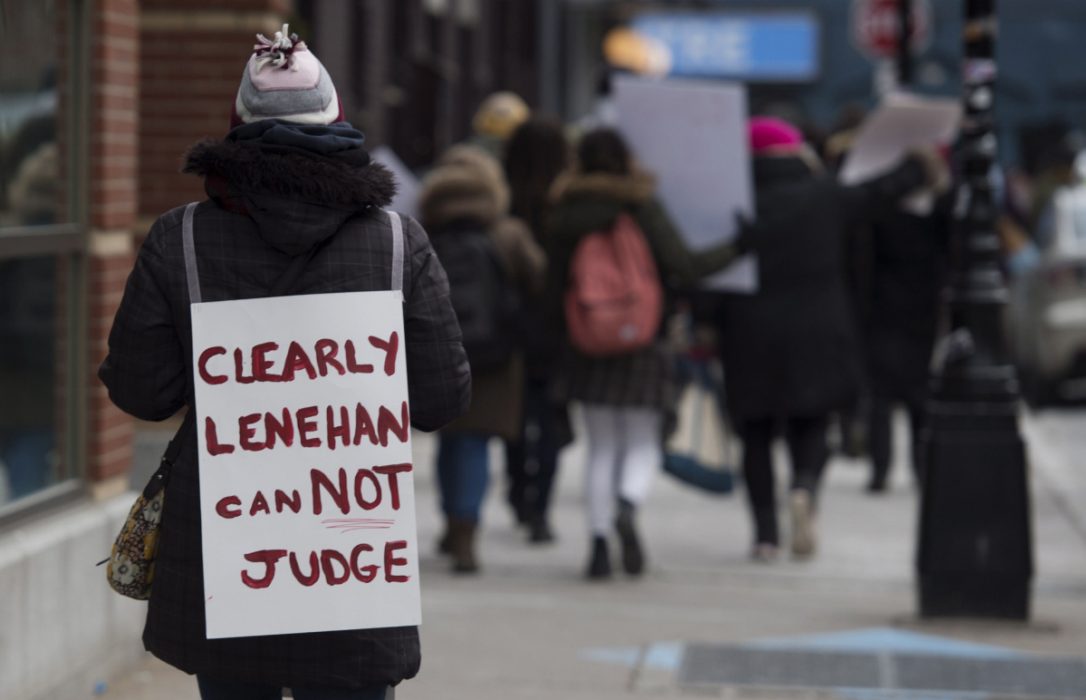

In early March, a Canadian provincial judge acquitted a taxi driver accused of sexually assaulting a female passenger in Nova Scotia. The woman had been found half-naked and unconscious in the back of his vehicle and had no recollection of being denied re-entry into a bar or hailing down a taxi. The driver was found by the police holding the woman’s trousers and underwear, having his pants down and unzipped, and with her DNA on his upper lip. After this two-day long trial, the judge stated that this [the driver] was not “somebody I would want my daughter driving with, nor any other young woman”, but his decision to dismiss the case was not changed because the defendant might have consented before passing out. A direct quote from the Judge published by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation reads “A person will be incapable of giving consent if she is unconscious or is so intoxicated by alcohol or drugs as to be incapable of understanding or perceiving the situation that presents itself […] This does not mean, however, that an intoxicated person cannot give consent to sexual activity. Clearly, a drunk can consent.” The victim in question had passed out and the alcohol level in her blood was nearly three times the legal limit to drive.

Demonstrators march downtown in Halifax over acquittal of taxi driver in rape case, credit: Darren Calabrese via The Canadian Press

A few days later, also in Canada but this time in the province of Alberta, former judge of the Federal Court resigned hours after the disciplinary body for Canadian judges recommended that he be removed from the bench. He had made headlines back in 2014 for his comments during a rape trial where he repeatedly asked the nineteen-year-old defendant “Why couldn’t you just keep your knees together?”. He also asked the woman, after she testified that the incident had happened over a bathroom sink, why she hadn’t sunk her “bottom down into the basin so he couldn’t penetrate you”. The judge acquitted the accused, only to see the Alberta court of appeal revert that ruling.

Still in Canada in the month of May, a Quebec judge made inappropriate comments during a sexual assault trial where he described the seventeen-year-old defendant as a “little overweight but has a pretty face”, and suggested that she may have been a “bit flattered” by the attention her alleged aggressor had given her, according to a recording published by the Journal of Montréal. He went on to say that different levels of consent are required for various actions, such as kissing or “putting one’s hand in the basket”, a French expression for grabbing someone’s butt. Although he did find the accused guilty of sexual assault, namely making unwanted sexual advances on the minor, the Quebec’s justice minister described such comments as “unacceptable” this past week.

A copy of the Canadian Crime Code sits inside a Courtroom in Toronto, credit: Toronto Star via Getty Images

I do not intend to call for a public hysteria fueled trial for these cases, nor do I intend to draw any conclusions as to what did or did not happen in those days in question. It is not on the alleged attacks themselves that I reflect upon but on the words and comments of the men who were responsible to trial the cases in an impartial manner. Why do these three “respectable” men still hold victim-blaming beliefs when the issue of rape and sexual assault are brought up? Can we put our trust in these judges, who unfortunately aren’t the only ones voicing such opinions, to serve justice and make sure the law is applied to all cases, without sexist pre-existing biases swerving their rulings?

With this, I do not mean to imply that the justice system doesn’t work and that all judges give out unfair verdicts, but the fact that these three incidents took place in half a year in the same country—one that is considered to be progressive—highlight how deep misogynistic stereotypes run in our society.