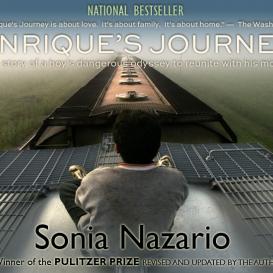

Today, 200 million migrants travel the world: every country is affected by waves of migrants leaving or arriving. In her book Enrique’s Journey, Sonia Nazario focuses on the so-called Northern Triangle’s – comprised of El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras – immigration to the United States of America.

Review: Enrique’s Journey by Sonia Nazario

Recent statistics concerning Central American immigration are difficult to find, but the Pew Research Centre reports that 11.3 million unauthorised immigrants were in the US in 2014, 49 per cent of which were from Mexico.

A year on, the Republican candidate for the US Presidency, Donald Trump, set the tone of his programme concerning Central American immigrants:

“They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us,” Trump said. “They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.”

He calls for the construction of a ‘tortilla curtain’, a wall at the Southern border which should be paid for by the Mexican government.

Hope amid the rhetoric

Sonia Nazario got the idea of writing Enrique’s Journey in 1997, when one morning she learned that Carmen, her cleaning lady, had four children in Guatemala, and that she had left them twelve years ago to work in the US.

In Los Angeles, a University of Southern California study from 1998 showed that 82 per cent of live-in nannies, and one in four housecleaners, are mothers who still have at least one child in their home country. The recent Republican anti-immigration rhetoric in the US serves to dehumanise and demonise immigrants, while ignoring the fact that, for them, the US represents hope.

Sonia’s book offers this new perspective, depicting how women sometimes sacrifice motherhood to work day and night in another country. They send the little money they make to their children for clothes, toys, education. Missing their mothers, children aged five to fifteen years old travel miles on top of trains, get robbed, raped, and sometimes die because they want to be reunited with their mothers.

Carmen’s story inspired Sonia Nazario to deepen her research around this phenomenon. Perhaps by reporting one’s strengths, courage, and humanity, readers might understand what immigrants go through. “I could take readers on top of these trains and show them what this modern-day immigrant journey is like, especially for children,” she states in her prologue.

Behind the writing

The process of writing the book was very complex. In May 2000, she scoped out shelters, jails, and churches in Mexico along the US border in order to find to find an immigrant child to retrace its journey. A nun in Nuevo Laredo contacted Sonia to tell her that a seventeen-year-old boy, Enrique, was heading north in search of his mother.

After a conversation on the phone, Sonia joined Enrique and spent two weeks shadowing him along the Rio Grande. From Enrique, she gleaned every possible detail about his life, noting every place he had gone, every experience, and every person he recalled who helped him. The next step was the most important one: travelling.

For five years, she talked to hundreds of children, to Enrique’s family, and to the people he met along the way. She made Enrique’s journey twice, riding trains like he did. Thanks to contacts from journalist friends, she managed to obtain a letter from the personal assistant of Mexico’s president to avoid jail and deportation. However, she would go to hotels at night and shower, eat and rest.

The third-person account

Sonia Nazario gives a unique insight into what his journey was like. What makes her book so extraordinary is the way she decides to present the story. Instead of writing a fiction in which Enrique speaks in the first person, Sonia tells the story from a different angle. The use of the third person is no hazard: her style is very neutral and reminds one of a documentary. Her role is only to tell the story, without any expression of feelings. This ‘outsider’ perspective gives the reader the impression that they’re travelling with Enrique, right by his side.

The book retraces Enrique’s journey and kills two birds with one stone. Indeed, Sonia chose Enrique because his journey is typical. By telling his story, the reporter tells the story of another 200,000 children who, each year, travel to find their mothers. Lourdes left Enrique when he was five, and started working illegally in the U.S, accumulating jobs paying $6 an hour.

She faces humiliation and poor life conditions to provide for her children. Meanwhile, Enrique misses a motherly figure growing up: he wishes someone would tell him to stay at school, to stop sniffing glue, to stop hanging out with gangs. His behaviour changes, he is kicked out of his family’s house, and he feels abandoned over and over again. He makes seven attempts to find his mother but is always deported.

On March 2, 2000, Enrique leaves for his eighth try. Will he make it this time?

Enrique leaves Honduras with only one direction in mind: north. Throughout the chapters, the reader shares Enrique’s experience as he is beaten up by gangs, freezes on top of trains, and starves for days. Sonia does not soften her tone while describing deaths and injuries. She uses brutal and crude words to describe pain as she witnessed it.

In parallel with Enrique’s story, she depicts what she witnessed herself and uses other immigrant’s testimonies to make her story more complete. For instance, women’s experience can be different from men’s: gang rapes are frequent and one out of six girls is sexually assaulted. Some girls try to pass like boys, some write on their chest ‘TENGO SIGA’ (‘I have AIDS’), while victims can go mad, get pregnant or commit suicide.

The boy rides trains, gets robbed, hides in bushes and asks for pesos to survive. He repeats those steps every day for months, like a routine. His mother pays a smuggler at the Nuevo Laredo border to reach the US soil. He crosses the Rio Grande, hides in a car and meets his mother’s boyfriend who will drive him home.

Just finished book Enrique’s Journey – very touching and it’s so important to understand the background to Hondurans migrating @SLNazario

— Ellie Wason (@ellie_wason) March 10, 2016

Simply human

The process of finding his mother, as impressive as it is, is not the most thrilling aspect. What makes his journey special is his mindset: so young yet so mature, the boy is driven by an unconditional love for his mother and is ready to do whatever it takes to be with her. Everytime the boy is close to giving up, the simple thought of being with his mother rekindle the flame.

But migrants’ stories rarely have a happy ending: those who managed to find their mothers still face many problems. Enrique leaves with Lourdes and accuses her of abandoning him, telling her that she is not his mother anymore. Children arriving in the US generally try to fill the lack of love by joining gangs, getting pregnant, or using drugs to forget. They realise their mothers are strangers. Enrique and Lourdes’ relationship is difficult: even if love prevails, they face a reality filled with conflicts and disillusionments.

The whole story provides a new perspective to the migrant’s journey, so often obscured in the headlines: ‘US Plans to deport some immigrant families who crossed Southern border’ or ‘Surge in Central American migrants at US border threatens repeat of 2014 crisis’.

Sonia’s message is not about how difficult the journey physically is, but rather how children manage to find strength and love to achieve their goals. The purpose of this book is to show that immigrants are simply humans, and that their 21st century odyssey is much more than riding trains illegally.

What do you think of Enrique’s Journey? Have your say in the comments section below.