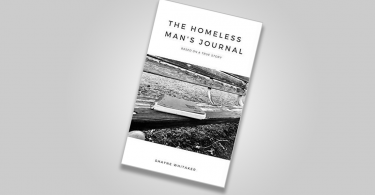

A campaign opposing the limit of twelve library books enforced upon prisoners has emerged victorious as HMS prison service announced that the cap was being scrapped. The Books for Prisoners Campaign, supported by many literary greats including Ian McEwan (Enduring Love ), Julian Barnes (The Sense of an Ending) and poet laureate Carol Ann Duffy, champions access to literature within prisons.

Using the brain and fighting boredom

Frances Cook, Chief Executive for the Howard League for Penal Reform, who is heading up the campaign together with English PEN stated: “This is an important victory for our campaign. It is encouraging that the government has recognised the important role that books can play in rehabilitation”. Whilst not the most obvious tool to utilise in regards to rehabilitation, there is strong evidence that diving into Dickens or becoming immersed in Ishiguro may help in rehabilitating prisoners. Unlike staring at a combination of pixels on a screen, reading requires you to use your brain.

A success for @TheHowardLeague campaign #booksforprisoners as Govt lifts limit http://t.co/Djok8MlvSg

— Frances Crook (@francescrook) November 8, 2014

A recent study carried out at Emory Univesity in Atlanta, United States concluded that becoming absored in a novel enhances connectivity in the brain, significantly improving brain function. With boredom often being rife amongst inmates, this can led to incidents of violence, vandalism and, in some extreme cases, assaults. Reading provides the stimulation many prisoners need in order to begin and persevere with their rehabiliatation back into society.

Benefits galore: employment, escapism and mental disorders

Ensuring that prisoners can obtain employment and earna steady wage is essential if they are to be successfully rehabilatated into life outside of the prison walls. However, in an already tough employment market, ex- inmates can be at even more of a disadvantage. In 2012-2013, the Prison Reform Trust identified that only 26% of prisoners secured employment upon their release from prison. Therefore, it is imperative that prisoners hone vital skills such as communication, analysing information, persistance and the ability to weigh up an argument whilst serving their sentence. All of these skills can be improved by reading frequently, making ex-prisoners more attractive prospects to potential employees.

Nothing compares to the feeling of escapism when immersed in a great book. For many of us, reading presents the chance to escape from the stresses of everyday life and leap into another time period, country or even an alternative universe. Perfect. Just the thought decreases your blood pressure. Researchers at Mindlab International based at the University of Sussex found that volunteers only needed to read for a total of six minutes to ease tension in their muscles and slow their heart rate. Overall, reading worked best as a technique to lower stress levels, reducing stress levels by 68% (on average), which is higher than other traditional methods of relaxation, such as listening to music or taking a walk.

You can totally lose yourself in a good book. All the more reason to allow them in. #booksforprisoners pic.twitter.com/IH9h6hy2vv

— Angi Mansi (@WorkPsychol) October 2, 2014

In 2004, an estimated 70% of prisoners were thought to suffer from two or more mental disorders. With such a high level of mental illness amongst offenders, it makes sense to use reading as a source to combat the drain of prison life on offenders’ mental health and aid them through the already challenging process of rehabilitation.

Combating a secular experience

Life whilst in prison is a very secular experience. Limited contact with friends, family and the goings on of the outside world results in a crippling sense of isolation for many prisoners. This can lead to unsuccessful attempts at rehabilitation back into life as a member of ordinary society. Once set free, ex- inmates find it difficult to adapt to “normal life” to the point where some end re- offending and consequently serve further time. What if this could be avoided? By reading books, prisoners are given a window to the outside world. They can travel across the globe, uncover new knowledge or find a character that they can’t help but emphasise with. The message of “you are not alone” seems invaluable in an atmosphere of solidarity, making the to rehabiliatation a little less daunting.

I strongly believe that books can play a part in the rehabilitation of prisoners. Books aren’t just mere objects for the purpose of enterntainment. Books educate, stimulate and above all, demostrate to all individuals the endless possibilites which life provides. This sense of opportunity and hope should be nutured during the rehabilitation of prisoners. As a ban on sending books to prisoners’ remains in place, we can only hope that the true power of books and the beneftis they pose to a prisoner’s rehabilitation is soon recognised.